Opening Preparation

Mark Dvoretsky and Artur Yusupov

With contributions from:

Sergei Dolmatov

Yuri Razuvaev

Boris Zlotnik

Aleksei Kosikov

Vladimir Vulfson

Translated by Joint Sugden

В. T. Batsford Ltd, London

First published 1994

© Mark Dvoretsky. Artur Yusupov 1994 Reprinted 1994, 1996 ISBN 0 7134 7509 9

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Ail rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, by any means, without prior permission of the publisher.

Typeset by John Nunn GM and printed in Great Britain by Redwood Books, Trowbridge, Wilts for the publishers, В. T. Batsford Ltd, 4 Fitzhardinge Street, London W1H0AH

A BATSFORD CHESS BOOK

Editorial Panel: Mark Dvoretsky, John Nunn, Jon Speclman

General Adviser: Raymond Keene OBE

Commissioning Editor: Graham Burgess

What chessplayer has not fallen into crafty opening traps? Who has not been caught out in some variation that seemed to have been discarded by theory long ago but is actually quite viable? Who has not fallen victim to his own prepared line, which, when tested, turns out to have a 'hole' in it? It has happened to all of us. Time and again we have come up against unexpected moves in the opening, and of course we arc perfectly familiar with the highly unpleasant feeling which results.

The search for unexpected ideas (that is, ideas new to the opponent!) is the fundamental source of developments in opening theory. And when you come to think of it, all our efforts in preparing for a game are directed precisely at finding something to puzzle, astonish and stun our opponent, something to force him off his normal course. Surprise him, and you will beat him! But then, our rivals are trying to do the same thing.

Of course, thorough opening preparation considerably reduces the probability that some opening move or variation will be a surprise to you. But it is impossible to prevent unpleasant shocks entirely, and you need to be mentally prepared for them.

One surprise is unlike another. By this I mean that a new move by the opponent may be objectively strong, or else it may be designed just for you, with your probable reaction in mind - for any surprise is first and foremost a blow to your nerves. A great deal depends on how quickly you recover and adjust your frame of mind to the full-blooded struggle. Mental disarray can lead to a quick collapse.

Incidentally, an encounter with the unexpected and unfamiliar is by no means always demoralising; it may. on the contrary, stimulate your imagination and compel your brain to work at full capacity. It quite often happens that the winner is not the player who catches his opponent in a prepared line, but the one who is caught! Relying wholly on the strength of his prepared analysis, a player may be incapable of extracting top performance from himself. In this case, anything unexpected in his opponent’s play, even something completely trivial, may be fatal to him - he simply cannot re-adjust to a lough, genuine contest.

I wish to elucidate this topic with examples from my own games. I shall begin with a game in the World Cup against the Hungarian Grandmaster Sax. Of course, players prepare very hard for such important encounters. I aimed to catch Sax out in a variation of the Queen's Indian which I had analysed fairly thoroughly.

Yusupov-Sax

Rotterdam World Cup 1989 Queen’s Indian Defence

|

1 |

d4 |

£f6 |

|

2 |

c4 |

еб |

|

3 |

b6 | |

|

4 |

g3 |

Даб |

|

5 |

b3 |

Apart from this, perhaps the most popular line, I have played 5 €ibd2 a few times.

5 ... ДЬ4+

6 £d2 Де7

What sense is there in Black’s loss of tempo? The point is that after b2-b3, the natural square for White’s bishop would have been b2. Later, perhaps, White will try to put his bishop on the long diagonal all the same, but on c3 it is less securely placed than on b2 and is also depriving the knight of its natural development square. On the other hand if White brings his knight out to c3, he will still have to remove his bishop from d2. So it turns out that Black’s manoeuvre doesn’t actually lose a tempo at all.

7 Ag2 c6

Preparing the advance ...d7-d5.

8 0-0 d5

9

Exploiting the fact that a capture on c4 is unplayable for the moment (owing to the vulnerability of c6), White attempts to seize the centre. The knight on c5 is extremely troublesome for Black, and he has to exchange it.

9 ... £fd7

Another move that seems to break the rules (Black moves the same piece twice in the opening), but in closed positions this is sometimes permissible. In this ease the struggle for the centre is more important than the quickest possible development of the pieces. And seeing that the knight on b8 is literally shackled by the knight on e5, Black’s move is in a sense a developing one.

10 2>xd7 £xd7

11 ДеЗ

This is what I told you about -White has to spend a tempo bringing his bishop onto the long diagonal. Incidentally, taking on c4 is still very dangerous for Black, since after 11...de 12 <15! cd 13 jLxgl White prevents him from castling and obtains a lasting initiative for the pawn.

11 ... 0-0

12 £d2 Sc8

At the time when the game was played, this move was almost considered obligatory, but present-day theorists are giving more and more thought to other lines. One of the new and good continuations is 12...ЗД6. This was first played by Portisch against Karpov (Rotterdam 1989), and afterwards Karpov used the same idea himself in his match against me. The position is quite intricate, despite its seeming simplicity, but we will not go into details now - that is what reference books are for.

13 e4

Playing for the centre! You may recall that in the Kasparov-Karpov matches of 1984/5 and 1986, Black tried answering with 13...b5, whereupon White played 14 Eel, but here Black employs a more popular plan.

13 ... c5

14 ed ed

15 de

White is not able to win a pawn; 15 Axd5 is met by 15...£lf6.

15 ... de

The present position has arisen more or less by force from 13...c5. If you are unfamiliar with it, fathoming its nuances over-the-board is not so simple. In principle, positions so critical for the opening variation ought to be studied in the most thorough fashion, and subjected to detailed analysis in home preparation.

16 c6

Here White has to reckon in the first place with 16...cb, since capturing on d7 is no good - the bishop on c3 is en prise. A sharp tactical skirmish begins, which I thought was not unfavourable to White.

16 ... cb!

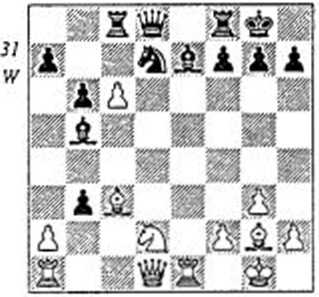

17 Eel ДЬ5(3/)

I dare say this is the most thematic. Sax attacks the pawn on c6; as before, he is unafraid of c6xd7. If White tries to sell his bishop more dearly with 18 £xg7 <2?xg7 19 cd, Black simply plays 19...Wxd7. He has the bishop pair, and it is not clear how to exploit the weakening of his position.

Now try to look ahead a little, to sec how play may develop and what resources arc at White's disposal.

What about 18 Eel ? This new move is worth thinking about.

How about taking on b3 with the pawn? Yes. this is not a bad rejoinder and may be best. I advise you to take a dose look at 18 ab for yourself. The variations arising from it are very interesting.

Anything else? As a matter of fact White can also capture on b3 with his knight, with an intriguing tactical idea in mind - Axg7!. It was this very possibility that I had been analysing before the game. A pity you did not spot it.

18 £}xb3! Дхсб

At this moment, I suddenly ceased to be happy about the way things stood. Sax was too willingly going into the complications, which - according to all my pre-game assessments - ought to turn out in my favour. He couldn’t be so naive as to go in for this sort of play without having something specific in mind! It dawned on me that there might turn out to be a flaw in my calculations. Sax, I repeat, had replied too confidently and quickly.

In such a situation the main thing is not to lose your head, not to panic. You must try to probe the position more deeply and find out what exactly the opponent is thinking of. It is also psychologically important to brace yourself for something unexpected, some unpleasant surprise.

Grasping al! this, I still didn’t see how I could refrain from capturing on g7 as planned. But I admit I played the move without my former optimism.

19 Axg7 <4’xg7

20 £d4! (32)

32 в

Let us together try to figure out Sax’s defensive idea. Black doesn’t have a wide choice here. Thus, 2O...Jif6 is no good - White simply gains the advantage with 21 Qxc6 Зхсб 22 Дхсб Дха! 23 <xal+. The main line that I had examined in my home analysis was, of course, 2O...£xg2, to which White replies with 21 ЗД5+ (other moves hardly deserve serious attention). There is no reason to fear 21...ФГ6, while after 21...ФЬ8 22 Exe7 White's attack gives the impression of being irresistible.

Indeed, how is Black to defend? 22...1h3 looks logical (23 Exd7? Wf6), but the king is on h8, so why not play 23 Wd4+ first? After 23...Г6 24 Sxd7 Wc8 25 2xh7+! ФхЬ7 26 Wh4+ and 27 Wxh3, Black’s position is not to be envied.

Then suddenly I saw 23...£3e5!. It turns out that this is what Sax was counting on! But nothing can be done about if, it is too late to back out.

|

20 ~ |

£xg2 |

|

21 £fS+ |

ФЬ8 |

|

22 Exe7 |

ДЬЗ |

|

23 Bd4+ |

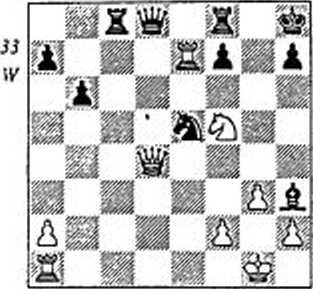

£e5! (33) |

Capturing on c5 with the queen looks unplayable, but White also has no wish to play an ending with equal material and the black bishop on h3.

At this point I had to think very hard before I succeeded in unearthing the saving idea. I was somewhat helped by the feeling that I had not

made any obvious mistake. Certainly I had played sharply and plunged into complications, but my previous play scarcely deserved such stem punishment as the inferior ending arising after 24 Sxc5 »’xd4 25 £lxd4.

24 #xe5+! f6

25 W’e2!

When you discover such an idea you feel a sense of relief, you realise that you have not been playing all that badly. The move played is more precise than 25 '«^cl, when Black would have 25...Zc7! (whereas now this can be met with 26 2dl). In addition, 25 ’ti,c2 sets up the threat of 26 Sxh7+.

25 ... AxfS

26 Zdl

The black queen is unexpectedly trapped. All the same, I had not caught Sax unawares. He had seen in advance the only defence by which Black - in turn - can save himself.

26 ... £g4!

Vi-%

White has various ways of drawing. For instance, he can play the pretty 27 Sxh7+ ФхЬ7 28 «’xg4 We8 29 Sd7+ Sf7 30 5xf7+ «xf7 31 Wxc8 ■&'xa2, and the queen ending is probably drawn. But there is no need for such elegance, and in the game I would have played more simply: 27 Zxd8 Дхе2 28 Zxf8+ Sxf8 29 Zxc2 Ef7, with full equality.

Imagine my astonishment when I learned that Sax had not thought up this whole idea himself but had taken it from a game Chernin-Browne, played in the tournament at Lugano a couple of weeks before the World Cup! Chernin, who had analysed this variation from White’s side, followed the same path as I did, came up against the same unpleasant novelty (which Browne may have found over-the-board), but then - unlike me - played 24 Zxe5 and drew the game after lengthy exertions. That is, he failed to find the right solution when confronted with an unexpected move. Perhaps he simply lost his nerve.

Clearly there are no recipes for all such occurrences. The main thing is not to lose your self-control but to search coolly for a weak point in your opponent's conception. And of course you must always be psychologically prepared for unexpected moves such as 23..ftSe5. I was greatly helped by sensing in good time that Sax had caught me out! When you realise what is in store, it is easier to find an antidote.

This game, of course, may give rise to some discouraging thoughts.

It demonstrates once again that with the abundance of information that saturates the modem chess world, it is sometimes quite impossible to keep abreast of all the latest developments in opening theory! Yet if you aim for distinguished results and at the same time have a liking for sharp, uncompromising variations, you cannot do without knowing the latest theoretical developments.

The next game we are going to examine is of a completely different character. In Yusupov-Sax, the players' opening knowledge reached as far as the transition to an endgame. This time, it peters out around move five!

Yusupov-Timman

Linares 1989 Slav Defence